A Peek into the Complexity of Asthma and Its Manifesting Features

Asthma is defined as a chronic inflammatory condition of the airways in which many cells and cellular elements are involved according to the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) Guidelines. It involves various cells and elements, characterized by immunological, inflammatory, metabolic, and remodeling pathways. It is a heterogeneous disease with different endotypes.

Asthma is caused by the failure of the respiratory and immune systems to develop normally, triggered by environmental triggers. It results in episodes of wheezing, dyspnea, chest tightness, coughing, and shortness of breath, leading to restlessness, fatigue, and reduced activity levels. 1

Episodes of an asthma attack are typically linked to a broad but fluctuating blockage of airflow, which is frequently reversible—either on its own or with medical intervention.

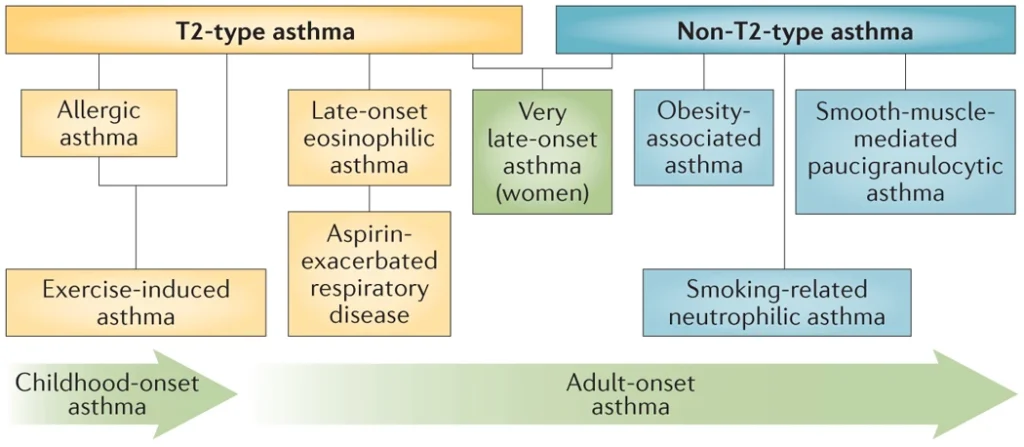

Understanding Variants of Asthma

Historically, asthma has been divided into two main forms: Allergic and Non-allergic asthma.

Allergic or T2-Type Asthma:

Triggered by environmental allergens, begins in childhood and persists into adulthood due to immune cell and organ behavior changes. Commonly triggered by environmental allergens, such as dust mites or pollen.

Non-allergic or Non-T2 Type Asthma:

A late-onset condition, is classified into Th2 and non-Th2 late-onset asthma, the former one characterized by recurrent rhinosinusitis, aspirin sensitivity, and high eosinophil numbers, while the latter is linked to obesity, aging, and smoking. 2

Unfolding Asthma Pathogenesis

It was believed that alterations in an individual’s acquired (adaptive) immune response were the only cause of asthma. According to recent research, asthma pathogenesis is significantly influenced by the innate immune system, which is not dependent on antigens.

Early Innate Immune Response Driving Asthma

Air pollutants trigger cytokine and chemokine production in epithelial cells, activating receptors such as toll-like receptors (TLRs) or protease-activated receptors (PARs). This leads to dendritic cells, innate immune cells, and mediators contributing to airway inflammation. 2

“Studies of asthma’s natural history have shown that almost 80% of cases begin during the first 6 years of life” 3

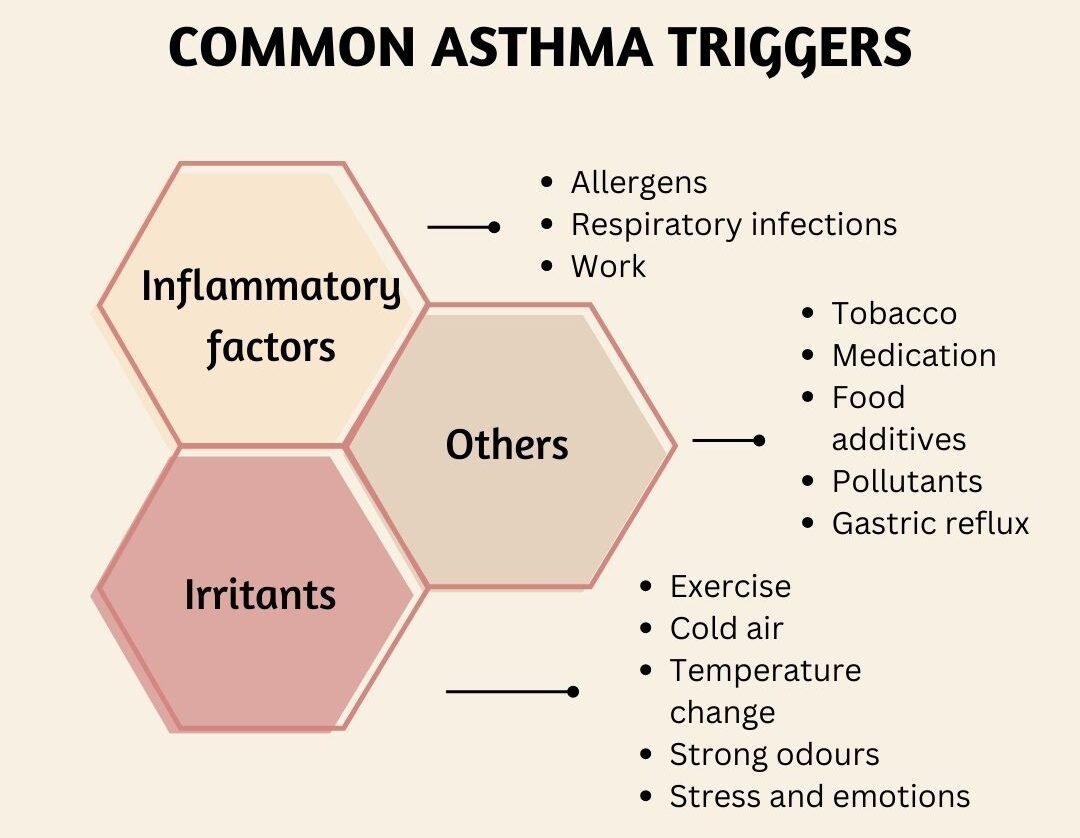

Asthma’s Provoking Risk Factors

Genetics & Family Medical History: Genetics significantly influences asthma and allergies, with genes like ORMDL3 linked across populations. Maternal and paternal asthma history strongly influences child asthma development. 4

Environmental and Perinatal Risk Factors:

Indoor allergens like dust mites, mold, and cockroaches increase asthma risk in children, with factors like prematurity, preterm birth, cesarean section delivery, low birth weight, maternal tobacco smoking, high sugar intake, neonatal jaundice, preeclampsia, and antibiotic use.

Gender:

Boys are more likely to develop asthma in childhood, especially before puberty, due to their smaller airways compared to girls before age 10. 3

Infections & Allergic Sensitization:

Childhood viral infections, antibiotic use, genetic variants, and immaturity in neonatal immune responses increase aeroallergen sensitization risk, leading to persistent asthma. Asthma is more prevalent in non-allergic individuals with elevated IgE levels. 5

Asthma Diagnosis

Common symptoms of asthma include wheezing, shortness of breath, cough, and chest tightness. Multiple testing methods are available to confirm airway obstruction and variability.

Pulmonary function testing or spirometry breathing test measures air expulsion, while bronchial provocation tests assess airway sensitivity. Spirometry with bronchodilator reversibility testing is the primary diagnostic tool. 6

Preventing Measures to Lower Risk of Asthma

Allergen avoidance:

Comprehensive allergen avoidance, including breastfeeding, low allergen diets, and dust mite reduction strategies, is most effective in genetically at-risk individuals, protecting them up to 18 years.

Dietary measures & Lifestyle:

Implementing early and ongoing strategies to prevent asthma, such as avoiding tobacco smoke, addressing obesity, and maintaining a balanced diet with adequate micronutrients like vitamin D, may be significantly helpful.

Microbial exposure:

Microbial exposure in diverse environments, like farms and rural areas, protects against asthma, on the contrary urbanization increases asthma prevalence. Probiotics and prebiotics reduce allergen sensitization risk, but effectiveness remains unclear.

Medical Interventions for Asthma Control

“Advances in asthma treatment, particularly personalized biologicals, have primarily focused on severe asthma in adults. Severe asthma is rare in children, accounting for only 2% of asthma cases.”

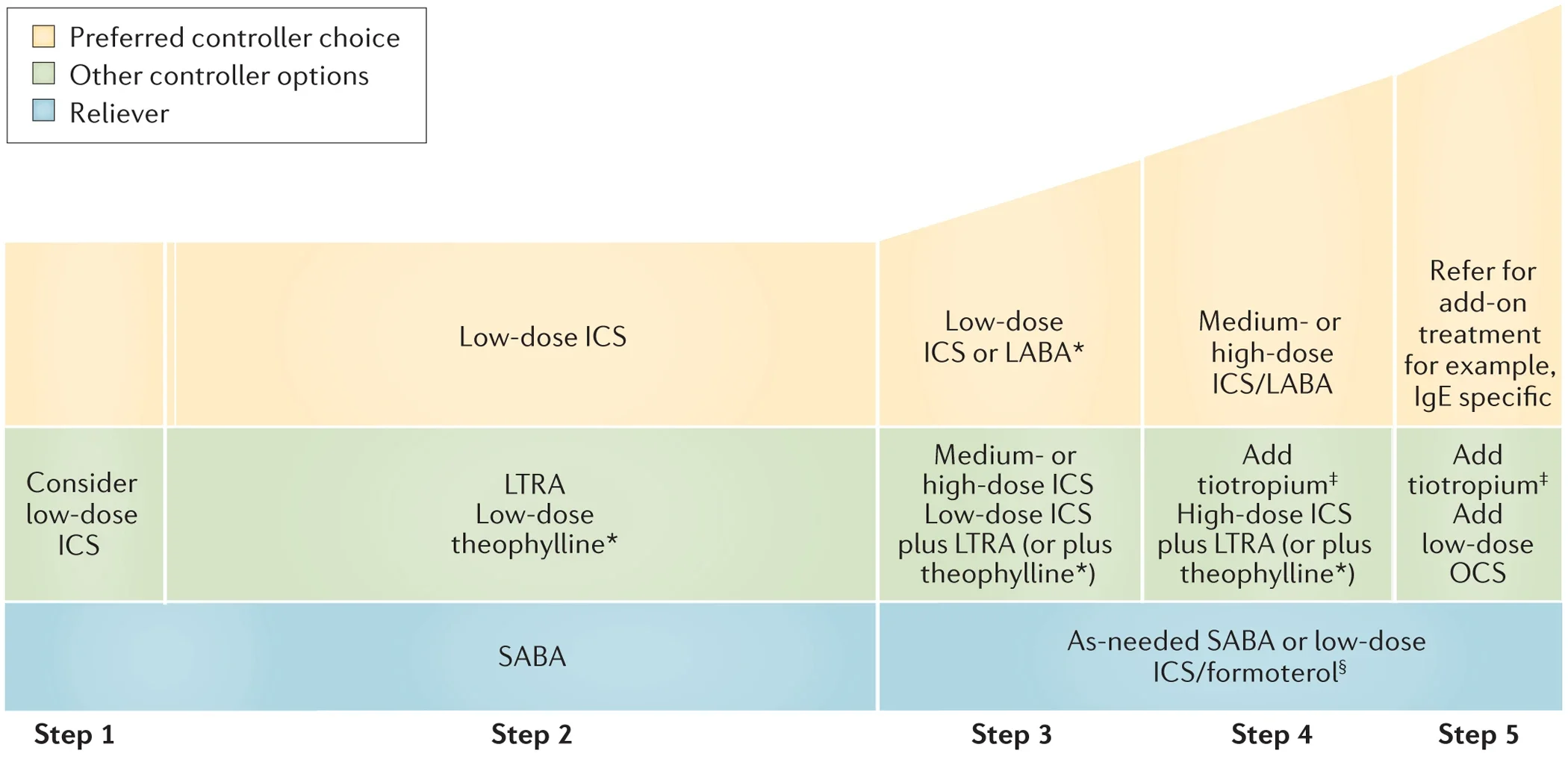

Asthma management has mainly two components; controller and reliever treatment:

i) Reliever (“rescue”) medication:

Used to quickly treat acute symptoms by opening airways, can help prevent asthma attacks and maintain control in mild cases, especially before physical exercise. Examples of this kind of medication are short-acting beta2-agonists.

ii) Controller (“preventer”) medication:

Works slowly over time and is taken regularly to prevent asthma attacks. Often containing steroids, used to prevent long-term asthma symptoms, even without acute symptoms. Examples of Asthma-controller medications include corticosteroids, beta2-agonists, and leukotriene antagonists.

Optimizing Asthma Management with Antifungal Therapy

Antifungal Intervention can improve asthma control, lung function, and symptoms by reducing airway fungal burden. It’s a promising treatment for allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) and severe asthma. (Note: ABPA) is a common fungal infection in uncontrolled asthmatics uncontrolled asthmatics.)

Antifungal therapy offers significant therapeutic benefits regardless of total IgE levels. Inhaled antifungals such as itraconazole and voriconazole, offer an alternative to oral ones avoiding systemic toxicities and adverse drug interactions. 8

Acing Asthma Treatment with GINA Guidelines

GINA guidelines provide global asthma recommendations based on severity and patient characteristics, adapting to local healthcare systems and practices, and ensuring they are adopted by national guidelines worldwide.

Emergency unit guidelines recommend bronchodilators administered by metered dose inhaler (MDI) and spacer for mild-moderate asthma, and nebulized therapy for severe asthma patients who urgently require a beta-agonist.

GINA’s new guidelines recommend inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) in combination with a long-acting β2-agonist (LABA) as reliever therapy for all asthma patients, regardless of severity. Formoterol is recommended as an LABA in combination therapy because of its prolonged and quick onset of action.

GINA does not recommend asthma patients being treated with short-acting β2-agonists (SABAs) in monotherapy because of the risks associated with using SABA alone and the possibility of overuse. 7

Step 1 involves the patient taking a low-dose ICS for symptom relief whenever they take their SABA;

Step 2 involves the patient taking an ICS daily;

Step 3 involves changing the maintenance treatment to a daily low-dose ICS-long-acting beta2-agonist (LABA);

Steps 4 and 5 involve increasing the amount of ICS-LABA. GINA recommends adding long-acting muscarinic antagonists and azithromycin, along with biologic therapies, in Step 5 for severe asthma treatment.

Managing Asthma During the COVID-19 Epidemic

Asthma patients are not at increased risk of COVID-19 or severe cases. They should continue taking prescribed asthma medicines and avoid nebulizers. Healthcare facilities should follow infection control procedures and COVID-19 testing recommendations.

GINA recommends COVID-19 vaccination for asthma patients, with precautions including allergy checks. Biological therapies should be given separately from the vaccine; it is advisable to provide biological therapy on a separate day from the COVID-19 vaccination. 9

Invision Medi Sciences offers a range of respiratory medications, including Chestoflo-F 250 Inhaler, Budesafe-F 400 Capsules/Inhaler, and Chestoflo-S250 Capsules, to ensure your respiratory well-being and confidence. Get in touch with us at 9341626732 / 9036398916 to obtain these drugs and feel free to breathe with assurance.

REFERENCES

- European Respiratory Journal 2003 21: 30s-35

- Cell 184, March 18, 2021 ª 2021 Elsevier Inc.

- Front Pediatr. 2019; 7: 256.

- Eur Clin Respir J. 2015; 2: 10.3402/ecrj.v2.24643.

- Eur Respir J 2000; 16: 609±614.

- European Respiratory Journal 2022 59: 2102730;

- Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023 Feb; 20(4): 3453.

- Clin Transl Allergy. 2020; 10: 46.

- Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022 Jan 1;205(1):17-35.

FAQs

How can asthma and COPD be distinguished from one another?

The daily morning production of phlegm from a cough is a distinctive feature of chronic bronchitis, a subtype of COPD. With asthma, wheezing fits and tightness in the chest are more common, especially at night.

What distinguishes the inflammation of COPD from asthma?

Chronic inflammation is a key pathophysiological factor in both asthma and COPD conditions. Activated mast cells/eosinophils and T helper 2 lymphocytes (Th2) are the main cell types in asthmatic airways. On the other hand, neutrophils and macrophages are crucial in the lungs and airways of COPD.

What are Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS)?

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), also known as glucocorticoids or steroids, are highly effective asthma controllers, suppressing inflammation in asthmatic airways even in low doses.

Which are the best medications for long-term asthma management?

The best medications for long-term asthma management are inhaled corticosteroids. These are not the same as the anabolic steroids used by bodybuilders.

What is a pulmonary antifungal treatment?

For the systemic treatment of pulmonary fungal illnesses, five triazoles—fluconazole, itraconazole, voriconazole, posaconazole, and isavuconazole—are presently licensed.

What is the standard first-line treatment for asthma as per GINA?

For patients with mild intermittent asthma, GINA suggests using short-acting beta2 agonists (SABAs) in combination with as-needed inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) for children aged six to eleven, and as-needed ICS/formoterol for adults.

What kind of steroid is budesonide?

Budesonide is a synthetic steroid belonging to the glucocorticoid family, known for its potent topical anti-inflammatory properties.

Which is best inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) or systemic antifungal therapy?

The mainstay of treatment for asthmatics is inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), recommended as first-line treatment to avoid respiratory exacerbations. Patients who have not responded to topical medication or who are at high risk of developing candidemia are advised to start systemic antifungal therapy as their first line of treatment.